It Could Definitely Happen Here

Many Americans struggle to accept that democracy is young, fragile, and could actually collapse – a lack of imagination that dangerously blunts the response to the Trumpist Right

“American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

I think about this quote a lot. It is from a speech James Baldwin delivered in October 1963, titled “A Talk to Teachers”. It is among the most profoundly true and insightful things anyone has ever said about the United States. Anyone who works and thinks about American history should adopt it as a guiding paradigm. And I believe it can also help us navigate this acutely perilous political moment in which we find ourselves right now. More various, more beautiful, more terrible. We need to grapple with all of these conflicting dimensions.

Just a few days to go. How is this election close? There are only two choices for president: A manifestly unfit, unqualified, vindictive wannabe-dictator who leads a coalition in which rightwing extremists are fully in charge and who openly promises fascism – or a totally normal, perfectly qualified, utterly non-radical liberal politician who leads a broad coalition that is committed to continuing constitutional self-government. How is this even remotely close?

There are a lot of structural reasons why expecting anyone to vanquish Donald Trump in a blowout is unrealistic. In a two-party system, especially one that operates under conditions of intense negative partisanship – meaning whatever partisans think of their own side, they despise the other even more –, any candidate starts with a floor of 40-ish percent, probably even higher, of the voting public.

Then there is the fact that the election is not happening on a level playing field. America does not have a fair, properly functioning democratic system. In fact, the system wasn’t designed to accommodate multiracial, pluralistic democracy – it consistently awards disproportionate power to a shrinking minority of white conservatives who are fully aligned behind the Republican Party. In 2016, Trump got three million fewer votes than his opponent Hillary Clinton – but won because his base of non-college educated white people, especially men, was perfectly distributed geographically, with a heavy concentration in key battleground states, to maximize his chances under the conditions of the Electoral College.

There are powerful un- or anti-democratic distortions beyond just the Electoral College: There is also the Senate (where disproportionate representation is particularly stark, as by about 2040, 70 percent of the country will be represented by just 30 senators, while less than one third of the electorate will get to determine 70 out of 100 members) and, of course, the Supreme Court (where the Republicans have established a hard-right majority with three of the six reactionary justices nominated by a president who lost the popular vote). If you add the escalating Republican state-level crusade to curtail democratic participation by specific groups via voter suppression tactics or gerrymandering, what you get is a situation in which one side simply doesn’t need anywhere near half the vote to gain power or at least make it a close election.

And yet, even under these circumstances, the election should be a lot less close, because Trump is extremely unpopular, and the clear majority of Americans does not want what he promises. That is not to say that there aren’t a lot of people – probably something like twenty to twenty-five percent of the electorate? – who are fully on board with Trumpism. Let’s call them the radical or extreme Right: Some are just fascists, or people who vehemently reject modern society and aggressively disdain multiracial, multi-religious pluralism. But there are not enough of them to win a presidential election.

There is another big bucket of people who, while not considering themselves rightwing extremists, are giving themselves permission to make common cause with the extreme Right by telling themselves radical measures are needed against what is supposedly the real, more acute threat: “the Left.” Historically, the extreme Right has basically never been able to get to power without the complicity of these more established, mainstream conservative circles.

“Deadly disbelief”

But there also remains a significant chunk of the electorate who cling to the idea that it won’t be so bad under Trump – for a variety of reasons. Some continue to vote for him because they consider all the warnings about authoritarianism and fascism as liberal hysteria and therefore believe it’s totally ok to prioritize their idiosyncratic personal interests (lower taxes for wealthy people, for instance). And some won’t vote at all, maybe because they are under the impression that there is no real difference between the parties, just two flavors of elite rule; or maybe they do dislike Trump more than Harris, but they simply don’t believe the danger emanating from Trump is real as they cannot imagine him implementing his crazy promises.

What they all share is the assumption that there is a massive disconnect between Trump’s proclamations (and those of the people around him) and what actually awaits America in case he gets back to the White House.

People who are heavily engaged in politics and see clearly who and what Trump is, often struggle to accept that such groups really exist. But they do. Two weeks ago, the New York Times portrayed what they called “The Trump Voters Who Don’t Believe Trump.” The Times quoted a bunch of people who had attended a speech Trump gave at the Detroit Economic Club – and they all agreed that whatever extremist declarations Trump was making on a nightly basis, it was “just for publicity,” just Trump “riling up the news.” Maybe they were simply lying to the reporters because they knew “respectable” people like themselves should not openly admit support for Trumpism?

That’s a part of it, certainly, with those business people at this particular event the Times visited. But there is also more going on here, as this general attitude is widespread across different demographics. According to the latest New York Times/Siena College poll, 41 percent of likely voters “agreed with the assessment that ‘people who are offended by Donald Trump take his words too seriously.’”

As Michael Podhorzer has recently outlined in great detail and with a wealth of empirical data, this “deadly disbelief,” as he calls it, could decide the election. Put simply, Democrats have won or done much better than expected in almost every election cycle since 2016 because a lot of people who don’t like either party nevertheless came out to vote – they voted *against Trump* rather than for a Democratic candidate. Podhorzer calls them “less-engaged anti-MAGA voters,” and indications are that they might not quite be mobilizing to the same extent they did in previous elections. What distinguishes them from “solid Harris supporters” is not that they dislike Trump any less or are more on board with his plans – the difference is purely that “they are much less likely to believe that Trump would actually follow through on those intentions,” and this significantly affects turnout among this group.

The Atlantic has recently called this phenomenon the “Trump Believability Gap”: No matter what part of the rightwing agenda – maybe something that is codified in Project 2025 – or which of Trump’s violent promises – using the military to suppress protests, for instance – people are confronted with, a significant percentage of them who vehemently reject the Trumpist agenda simply do not believe that anything like that could actually become reality.

How bad could it possibly be?

One of the most frustrating things about U.S. politics is that people who aren’t engaging with it much will look at you like you are some kooky leftist propagandist if you simply outline what the Republican Party is doing wherever it is in charge and explicitly promises to be doing in the future. It’s difficult to convey to people how much the GOP has radicalized, how much the power centers of conservative politics are in the hands of extremists, how much the rightwing intellectual sphere is dominated by some really radical ideas that are being pushed into the mainstream.

There are many people and institutions that have actively contributed to obscuring what has been happening on the Right. There is mainstream media’s insistence on distorting everything through a normalizing prism, all in service of “balanced” coverage that allows them to remain “neutral” and uphold the idea that politics is a game between two essentially equal teams, Team Red and Team Blue – the dogma on which all the conventions of “respectable” political coverage are built.

There is also a whole industry of professional anti-“alarmists” whose public standing and success is built entirely on reflexively pushing back against “leftwing hysteria.” It is all hyperbole, they say, because the Republican Party isn’t that bad, or because maybe it is, but the mythical guardrails are working. It should be clear by now that these self-proclaimed arbiters of reason will not change their tune (“Don’t be silly, there will be no Trump coup!” – right before the 2020 election; or: “Nothing to see here, democracy is totally fine, there was never any real threat!” – right after the 2022 midterms), regardless of how straightforward the evidence in front of them.

They have been so consistently wrong, and yet polite society can’t seem to quit these oracles. Why is their message that things are fine, thank you, so attractive when it is so obviously belied by the political reality around us? There is a powerful normalcy bias that is hard to overcome. In a lot of ways, things really are “normal,” in the sense that most of us continue the routines that dominate our daily lives, even in the midst of a political crisis around us. The experiences of most Americans, even those who follow politics somewhat closely, tend to be shaped not just by the political upheavals, but by the normal challenges of everyday life. Stores remain open, people have to go to work, they suffer or celebrate with their favorite sports teams. In any case, we have to function. People need to live their own lives, deal with their own struggles, take care of themselves and their families. And so, we compartmentalize, which often leads us to experience a strange mixture of normalcy and emergency that can sometimes feel almost disorienting. There is always a temptation to resolve that tension by ignoring the emergency and focusing on the ordinariness of it all – because how bad could things possibly be? It is eminently difficult for contemporaries to discern the exact nature and extent of the crisis through which they are living. We can’t necessarily see the slide towards authoritarianism by simply looking out the window – certainly not until it may be too late.

American exceptionalism, progress gospel, and historical illiteracy

There is more going on than just normalcy bias, however. The “Trump Believability Gap” is evidence of a pervasive inability to imagine that things really could get significantly worse. It cannot happen here! Or not anymore, anyways. It is the result of a rather disastrous mix of a deep-seated mythology of American exceptionalism, progress gospel, lack of political understanding, and (willful) historical ignorance.

In its purest form, the myth of American exceptionalism holds that Americans are essentially immune to authoritarianism of any kind – the “soul of the nation” won’t allow it, or the country’s DNA, or the freedom-loving national character… The political mainstream has generally – or at least rhetorically – moved to a slightly more nuanced understanding of the American story. But the collective imaginary is very much still grounded in exceptionalist ideas. Just think of how many times you have heard politicians utter the phrase “This is not who we are!” when referring to racism and white supremacy.

Exceptionalism lingers. And it has warped many people’s understanding of U.S. history. In June 2021, for instance, leading Never Trumper Bill Kristol posted on ex-Twitter: “We’re the world’s oldest democracy. It’s hard for us Americans to take threats of coups and even the dangers of authoritarianism seriously. But it's time to do so.” I’m not bringing this up to single out Kristol, specifically: I wish I had a dollar for every time I have encountered versions of this argument in personal conversations with journalists, politicians, neighbors (and Kristol, at least, acknowledges that it’s high time to abandon such notions).

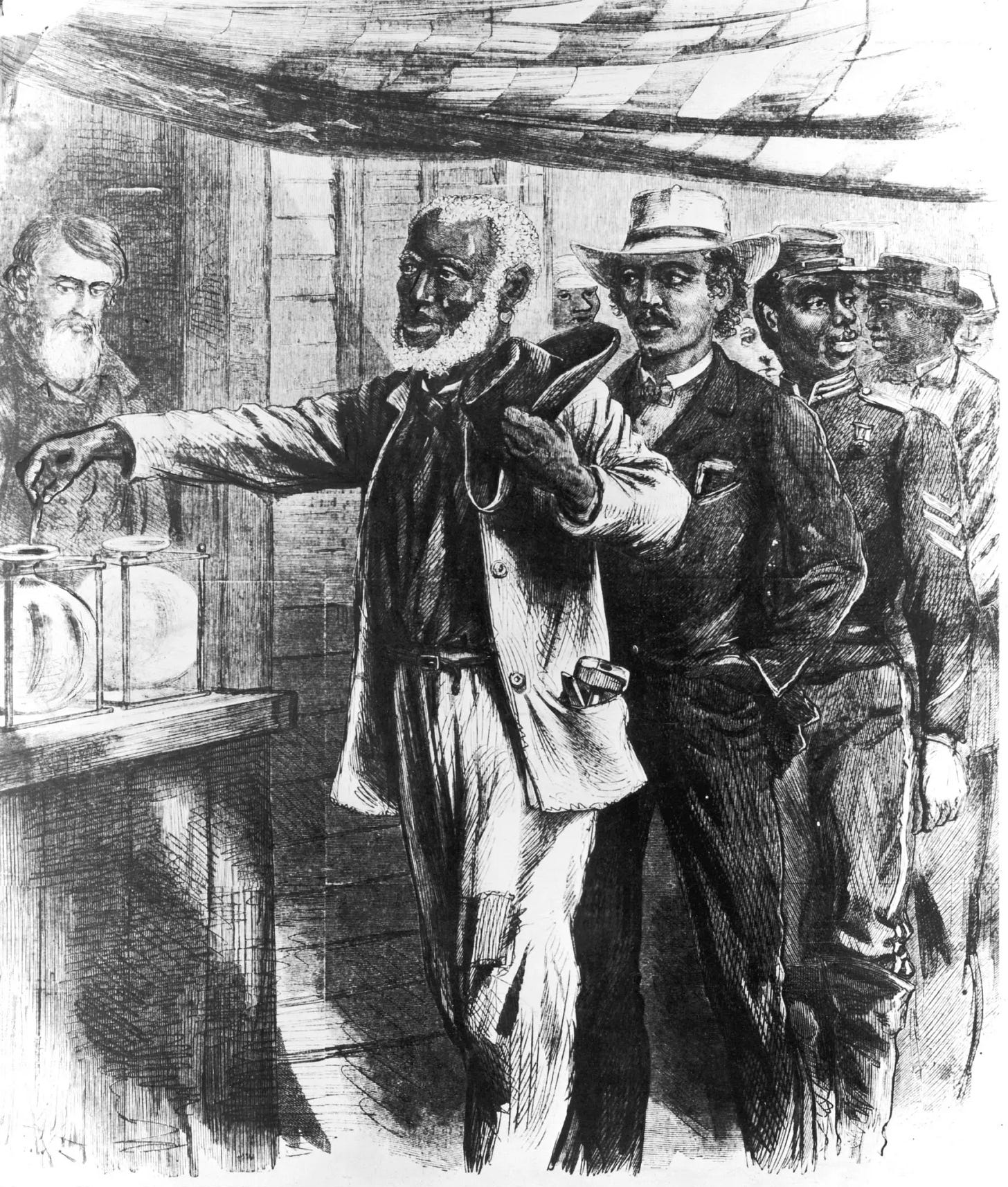

The statement perfectly captures two central themes of the exceptionalist mythology that blunts the response to the Trumpist threat: “We” have always been a democracy; therefore “we” simply don’t have any experience with authoritarianism. But the defining question in U.S. history has always been: Who is “We”? For most of America’s existence, and until quite recently, those who lived within the nation’s borders and happened not to be white men had plenty of experience with state authoritarianism. Significant parts of the country existed first as a slavocracy and then, after a brief interlude during Reconstruction, as a one-party apartheid regime during the so-called Jim Crow era. During the same period, Native Americans were disenfranchised, dispossessed, and persecuted by the American state. It is certainly true that even before the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, the American political system was fairly democratic, at least by contemporaneous international comparison, if a person happened to be a white Christian man – but it was something else entirely if they were not.

This is not some ancient history. There are a lot of people voting in this election who remember disenfranchisement and state-enforced racial segregation all too well as the defining features of their own youth. Nor was American authoritarianism ever just a regional issue, it was never confined to “just” the South. Slave-holding elites exerted a dominating influence over the Republic before the Civil War, and Southern segregationists were immensely powerful in national politics until the 1960s. Moreover, there is a strong domestic tradition of white nationalist, white supremacist extremism across the country. The Ku Klux Klan was very much a national organization in the 1920s; because of Trump’s bizarro extremist rally at Madison Square Garden, a lot of people rightfully brought up the fact that 20,000 people attended a Nazi rally at the exact same place in February 1939; in the 1960s, George Wallace quickly realized that his fight against racial equality resonated with white voters far beyond the South; and a well-established far-right grassroots activism has shaped political culture on the ground across post-war America.

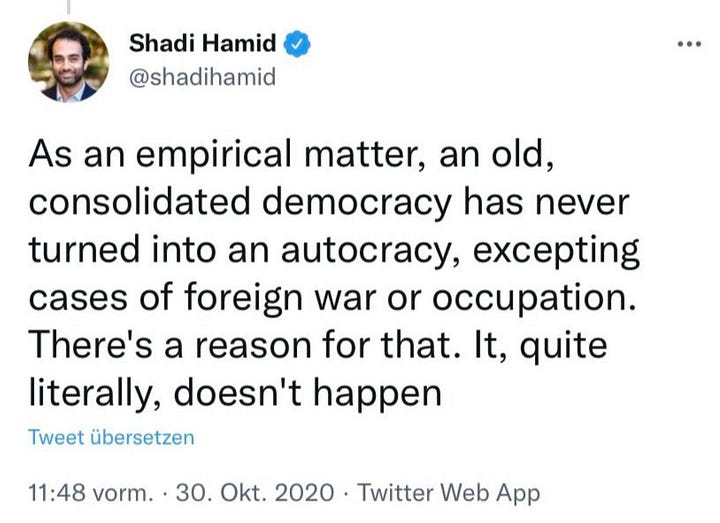

Despite all of that, highly educated people with massive platforms like Shadi Hamid, who gets to shape the political discourse from his influential position as opinion columnist and member of the Washington Post’s editorial board, will relentlessly mock anyone who suggests that maybe the threat of extremism and authoritarianism is real, that perhaps it could actually happen here. Nah, according to Hamid, that’s all just hysteria, a “moral panic,” as he said after the 2022 midterms. Even now, in his latest column, Hamid dismisses the idea that this could actually be a historically important election and offers this as advice: “no one should cry about an election. The worst thing about elections is losing, but the best thing about losing is that you live to fight another day – in the next election.”

Hamid’s casually ignorant confidence is built on the idea that because of the nation’s supposedly glorious, centuries-long democratic tradition, it is simply definitionally impossible for authoritarianism to succeed in America. Just days before the 2020 election, he opined: “As an empirical matter, an old, consolidated democracy has never turned into an autocracy, excepting cases of foreign war or occupation. There’s a reason for that. It, quite literally, doesn’t happen.”

Multiracial, pluralistic democracy is young and fragile

The very obvious flaw in this argument, if we even want to call this most abstract and superficial of observations an argument, is that the political system that was stable for most of U.S. history was a white man’s democracy, or racial caste democracy. There is absolutely nothing old or consolidated about *multiracial, pluralistic democracy* in America. It, quite literally, only started less than 60 years ago, and because the staunchly anti-democratic, anti-egalitarian, anti-pluralistic ideas that have always shaped the American story didn’t just vanish into thin air with the passage of civil rights legislation of 1964/65, the conflict over whether or not it should be allowed to endure and prosper has been the central fault line in U.S. politics ever since.

The actual takeaway from U.S. history should not be that we are, today, merely dealing with residual ant-democratic tendencies that haven’t been defeated just yet. The point is that we must not assume directionality in history at all. There is no arc, and there definitely is no ironclad law of the universe that says “We” can’t slide back – or slide forward into a new kind of authoritarianism. That is why Reconstruction is such a key historical reference. The Reconstruction period immediately after the Civil War through the mid- to late 1870s was the exception from the norm of a racial caste democracy. It was an unprecedented experiment in biracial democracy – brief, but breathtaking in its impact. Amongst white Americans, there was a widespread expectations that formerly enslaved people would probably not know what to do with their newly acquired rights, that it would take time. But in reality, voter turnout among Black people was extremely high. About 2,000 Black men were elected to public office on all levels – Mississippi even sent two Black senators to Congress. South Carolina, the heart of the former Confederacy, elected a majority Black state legislature in 1868. And beyond just politics in a narrow sense, African American social and cultural life soared in those years. Here was the glimpse of what an actually democratic society might look like.

But it did not last. America’s first attempt at biracial democracy was quickly drowned in ostensibly “race-neutral” laws and almost unimaginable levels of white reactionary violence. After Reconstruction, the country was dominated for decades by a white elite consensus to not only leave the brutal apartheid regime in the South untouched, but to uphold white Christian patriarchal rule across the nation. The level of biracial equality and democratic participation the South experienced during Reconstruction would not be reached again until almost a full century later. There would not be another Black senator in Congress until 1967; the South did not elect another Black person to the Senate until 2013.

The lesson here, if there is one, is not that progress is impossible. There has been tremendous progress at times! Courageous people have achieved marvelous things, often at incredible risk and devastating personal cost. But nothing is ever guaranteed, there is no linear progression, no end goal we are destined to reach somehow. You may object that in the long run, things did get better, did they not? Well, that’s a matter of perspective and timeframe. If you compare the 1890s or even 1950s to today, then yes, absolutely, America is a much more democratic, fairer society. But what if we set the temporal parameters differently: What if we compare the situation of anyone who was not white in 1930, 1940, or even 1950 to the height of Reconstruction? Tens of millions of people lived their entire lives in those decades. The America they experienced was not a democracy, it wasn’t getting better. In fact, they would have been told stories of that brief but marvelous moment, right after the Civil War, when “We” experienced democracy (a very different “We” then the exceptionalist “We” that speaks of America’s glorious democratic tradition going back hundreds of years).

We are now once again at a point when the clock might just be turned back significantly, whether or not Americans will admit that’s a real possibility with ample precedence in their own history. Most people didn’t believe Trump would become president. Most people believed a peaceful transfer of power was a given. Most people didn’t believe the Supreme Court would actually overturn Roe v. Wade. Almost no one believed the same Court would declare Trump functionally immune from criminal prosecution. And now, a significant portion of Americans cling to the idea that all those hideous things the Right is promising – including the ethnic cleansing of the nation and the use of the military to oppress protests – simply cannot happen here. But at some point, we all have to grapple earnestly with the fact that the radicalization of the American Right has recently outpaced what even critical observers thought was likely. “They are not going to go *that* far” has been proven wrong over and over again.

It really can happen here.

The “It” is unlikely to be a fascist dictatorship that looks exactly like 1930s Germany. But people need to accept that things can change – in either direction: It really could get much, much worse. But it could also get better. There is nothing inevitable about either doom or progress. We are neither fated nor guaranteed to experience the status quo for all eternity. There is something deeply unsettling about this realization: There is no moral arc of the universe, progress can always be reversed, victories are never guaranteed to last. But it should also be empowering and, at the very least, create the sense of urgency that is needed to defend democracy, as flawed as it currently is, and propel America forward.

“American history,” remember, “is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

I grew up in a small, rural Indiana town not so long ago. My stepfather was a white supremacist, complete with Klan membership and gown & hood. My siblings & I were forced to listen to his hate filled rants at every meal. That is, when we weren’t being dragged to church 6 days a week as part of our mother’s adoption of an evilangelical cult’s agenda soaked in hate, fear, racism, bigotry and misogyny. It was hell.

Watching the country I served in uniform for ten years turn into a nationwide form of my childhood, of everything I tried to escape, has been devastating. I am not at all surprised though. Hate is an easy sell - it’s addictive and feeds on itself. Hate feels powerful and is far, far easier than paying attention, being self aware and doing the work of not blindly following anyone, of trying to contribute to society for the good of everyone.

Just imagine what amazing heights we could reach if all the energy put into hate, fear and hurting others was instead directed towards a just society for all. Will humanity ever do that? I hold out a sliver of hope but highly doubt it.

I am a lawyer, member of the US Supreme Court Bar, and taught US history and government for 25 years. After repeated teachings of our nation's history aits many incarnations year after year for a quarter of a century, I agree with your article. We are indeed not immune to this incipient fascist virus. MAGA's desire to ban the teaching of slavery reminds me of my high school history text book in Dallas in the 1950s where there was a picture of "happy slaves dancing in the fields" along with laudatory tales of Civil War generals. As a Jew I was puzzled that there was no mention of Hitler's final solution and only two paragraphs about his beliefs. I also recall as a 6 year old having to "sign" a card pledging "I was not now nor had I ever been a member of a Communist group" in order to begin first grade. I fear my time with my students has not been deep enough to supplant FOX, NewsMax, Newsnation, Breitbart, Sinclair radio stations, the NY Post, Bill O'Reilly, Tucker Carlson, and on and on. Hopefully we get another reboot and Harris will prevail. But what then? Demand all citizens retake civics? And taught by whom?