If It’s Really That Bad, People Need To Know

Unless America’s leading institutions act accordingly, why would anyone believe Trump is a serious criminal threat - or that the danger to democracy is really all that severe?

On Saturday, Donald Trump used his social media propaganda platform to ask his followers “TO TAKE OUR NATION BACK” – an unmistakable call for violence reminiscent of previous such actions by the former president, specifically prior to January 6. What’s all this about? Trump said he was going to be arrested on Tuesday. He didn’t offer any evidence or specifics. But he did, of course, start using his supposedly imminent arrest as a fundraising pitch.

It's important to remember that nothing has actually happened yet. Still, America is back to debating a question that, in a healthy democratic culture, really is not supposed to be one: Should the president be held accountable for committing crimes? Trump has exacerbated, but not caused that debate. It is hard not to see the Nixon pardon as a crucial moment in the evolution of this peculiar kind of presidential impunity and how it’s infected America’s political system and culture. With Trump, there is so much crime that we are now debating a new variant of this question: Should he be held accountable for *this* crime even though it pales in comparison with other, more severe crimes for which he’s not been held accountable yet?

I don’t want to make light of the situation. The threat of violence is real, it is important to think through the dangers and pitfalls of criminal prosecution. The last time we had this debate was not even three months ago, after the January 6 Committee had announced its decision to refer Trump to the Department of Justice for prosecution. Nicholas Grossman provided a great overview of the potential arguments against such a course of action – and why it was still necessary to go ahead and prosecute anyway. We also tackled this question extensively in Episode 8 of “Is This Democracy,” coming to a similar conclusion.

The situation is different now, three months later, as we are talking about a different crime, one not directly associated with a violent assault on the transfer of power – in this case, an illegal payment to a porn star before the 2016 election. But in general, the case against prosecution rests too much on the dangers of acting while not paying enough attention to the dangers of inaction. Although, “inaction” is not even the right term: Not prosecuting Trump is a decision – one that comes with severe political consequences also.

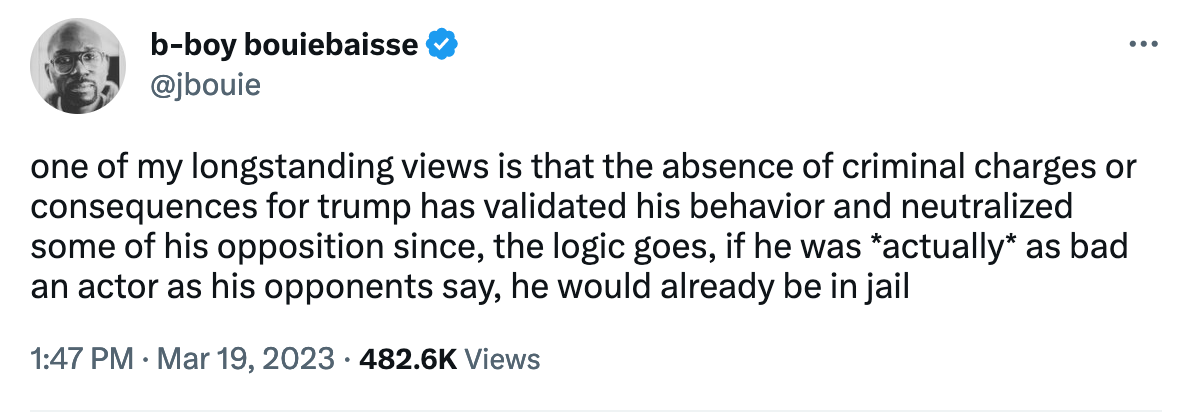

Jamelle Bouie precisely captured what I believe is the core issue: “one of my longstanding views,” Jamelle wrote on Twitter, “is that the absence of criminal charges or consequences for trump has validated his behavior and neutralized some of his opposition since, the logic goes, if he was *actually* as bad an actor as his opponents say, he would already be in jail.” He continued in another tweet: “instead of drawing people to him, arresting and charging trump would underscore the critique and strengthen his opponents, imo.”

I think this is spot on – and this general dynamic actually extends well beyond just Trump: to the Republican Party, to the American Right, to the people and institutions chiefly responsible for the assault on American democracy and the attempts to roll back the post-1960s civil rights order. If it was really as bad as people on “the Left” say, if the situation was as dire and dangerous as democracy scholars like myself claim, wouldn’t that be reflected more clearly in the way the leading institutions of American life act, especially those specifically tasked with upholding democracy and the rule of law?

If we zoom out a little bit, one of the key challenges since the start of the Trump era has been how to communicate effectively to the American public that something other than “politics as usual” is going on, that the threat of democratic erosion is real. There are many reasons why that’s such a difficult task, starting with the general political context in which everything is perceived as a partisan attack and the fact that the majority of Republican voters exist in near-impenetrable rightwing information environments. The biggest question isn’t even how to reach or “convince” Trump’s base, which seems like an entirely unrealistic expectation. It’s how to overcome the intense normalcy bias that keeps too many people in the (small-d) democratic camp – including Republican voters who still like to considers themselves in that group – from accepting what’s at stake.

The experiences of most Americans, even those who follow politics somewhat closely, tend to be shaped not just by the political upheavals, but by the normal challenges of everyday life. Stores remain open, people have to go to work, they suffer or celebrate with their favorite sports teams. It would be unfair to denounce these as just illusions of normalcy. In a lot of ways, things really are “normal,” in the sense that most of us continue the routines that dominate our daily lives, even in the midst of a political crisis around us. We have to function, we compartmentalize, we experience a strange mixture of normalcy and emergency that can sometimes feel almost disorienting. Bohemian novelist Franz Kafka famously noted in his diary on Sunday, August 2, 1914: “Germany has declared war on Russia. Swimming lessons in the afternoon.” Kafka had just witnessed a crucial step in a conflict that quickly escalated into what contemporaries called the Great War – the First World War. His laconic remark captures the tension between the global and the personal, the extraordinary and the routine, history and everyday life, the outrageous and the mundane.

There is always a temptation to resolve that tension by ignoring the emergency and focusing on the ordinariness of it all – because how bad could things possibly be? The sky isn’t actually falling. It is eminently difficult for contemporaries to discern the exact nature and extent of the crisis through which they are living. We can’t necessarily see the slide towards authoritarianism by simply looking out the window – certainly not until it may be too late – but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a continuing crisis underneath.

We can complain about how too many people are complacent. I do it all the time. And it is only fair to note that *not* taking the political situation seriously is a luxury only those can afford who are not immediately threatened by the anti-democratic radicalization of the Republican Party. It is a privilege not available to the women who are dealing with the cruel consequences of their bodily autonomy being denied, or the traditionally marginalized, vulnerable groups who are the key targets of the reactionary offensive against the post-1960s civil rights order.

But let’s not assume that everyone who isn’t already grasping the acute danger, and hasn’t developed the same sense of alarm that I think is fully warranted, just doesn’t care. People need to live their own lives, deal with their own struggles, take care of themselves and their families. We all grind through our normal routines, we have to – unless something disrupts “normalcy.”

That, to me, is the crucial question: How do we pierce that sense of “normalcy”? How do we create moments of meaningful disruption? Elite signaling plays an enormously important role here. The signal that it’s time to break through the routines has to come from the top.

That’s partly why the public hearings of the January 6 Committee were so important – why it was crucial to make them into a well-produced spectacle. It was the right signal to send: This isn’t normal. This is what the nation needs to care about. President Biden’s big democracy speeches last fall served a similar purpose. His “Soul of the Nation” speech in Philadelphia in early September, in particular, was a public intervention designed to disrupt the veneer of “normalcy.”

If there is such a thing as the rule of law, then being caught committing a crime needs to lead to consequences. If there is such a thing as a democracy, then it is of particular importance that those in positions of power have to face consequences for committing a crime. Since we are talking about consequences for someone who is not just the former president, but one of the leaders of the Right, someone who has a devoted mass following that displays cult-like and fascistic tendencies, the situation is inherently fraught. But it is not the demand for accountability that makes it politically delicate – the alternative is not to defuse and neutralize the situation via inaction.

It is not just the ex-president’s supporters we need to worry about: what they will make of all of this, whether or not they will ever again trust the Department of Justice or law enforcement officials. In general, American politics has been deferring to their perceptions of reality, their political, social, and cultural sensibilities rather too much. We should also worry about the rest of the country, the majority, even though it is comprised of people who do not threaten violence every time someone questions their supposed right to shape all spheres of American life in their own image. What do we signal to them – about whether or not the system can still be trusted, about the state of politics and how bad, serious, or concerning the situation really is?

To paraphrase what Jamelle Bouie said: If we assume that this is still a country with functioning institutions, then it’s only logical to conclude that Trump walking free means his transgressions can’t be that bad. Holding Trump accountable via criminal prosecution would be unprecedented in some ways and potentially disruptive. But at some point, it becomes really hard to expect people to break through their apolitical routines and actively defend democracy, as is necessary in a situation of crisis, if the institutions we ask them to trust shy away from doing their part – if they instead continue to signal “normalcy,” that politics as usual is still an option or, at the very least, right around the corner.

Thank you for this! It is worth noting that many Americans live in states that are not functioning democracies. Tennessee (where I recently relocated) is one of them, and I have already been bowled over by this state’s race-targeted voter suppression and gerrymandering, its dehumanizing forced-birth and transphobic laws, and its overwhelmingly white state legislature rearranging the political processes of cities with significant Black populations.

I think this may help explain the tendency to normalize what is happening to this country. When your state is already operated as a non-democracy, it’s harder to get exercised--easier to be cynical--about losing democracy at the federal level.

Excellent points, too often left unsaid. Until people realize that they, or their children or loved ones, are actually in danger they (we) will continue to just live as normal.

“Elite signaling” to me means LEADERSHIP. And that is exactly what the takeover of American politics by a two-party-system has denied the nation. Leadership. So that will have to rise from another corner. Perhaps the labor movement. Maybe elsewhere. But we need that leadership, that “signaling” soon...now!